3 Timeless Russian Painters Who Shaped a Brilliant Artistic Legacy

Meet 3 timeless Russian painters - Roerich, Korovin, and Gorbatov - whose art defined an era and continues to attract collectors around the world.

Table of Contents

Russian art of the 20th century produced some of the world’s most visionary painters. Among them were Nicholas Roerich, Konstantin Korovin and Konstantin Gorbatov – three masters who not only created beautiful works but also embodied the spirit of their time. Each was a Russian artist of great scope: Roerich with his mysticism and cultural politics, Korovin with his impressionism and theatricality, Gorbatov with his post-impressionist landscapes and folk motifs. They lived through the twilight of Imperial St Petersburg, the October Revolution and the émigré life in Europe.

Today their paintings are in museums and private collections and prove that their work is timeless and loved by art lovers and collectors alike.

Between Empire and Exile: The Rise of Russian Art in the 20th Century

The world that shaped Roerich, Korovin, and Gorbatov was one of dramatic change. In the late 1800s, Russia’s cultural centers – Moscow and St. Petersburg – fostered thriving art movements and societies. Influential groups like the Peredvizhniki (the “Wanderers”) championed realist depictions of Russian life, while the Mir Iskusstva (“World of Art”) group led by Sergei Diaghilev promoted artistic innovation, cosmopolitan styles, and a renewed interest in Russia’s heritage.

This iconic painting depicts members of the World of Art circle, including Diaghilev, Benois, Bakst, and other cultural figures who shaped the evolution of Russian art at the turn of the 20th century.

All three of our artists were touched by these currents: Roerich and Korovin were active in the World of Art circle, and even Gorbatov exhibited with the Peredvizhniki (en.wikipedia.org). It was a period of cross-pollination – French Impressionism had made its way to Russia, traditional Orthodox Church iconography was being rediscovered, and Symbolist poets and painters were infusing art with spirituality and myth.

But the 20th century also brought war and revolution. First World War and 1917 revolutions shook Russian society. As the Soviet Union rose from the ruins of the Russian Empire many artists faced ideological pressures or material difficulties.

Mural mosaic on the Church of the Holy Spirit in Talashkino, designed in a Neo-Russian and Symbolist style. This work embodies the fusion of Orthodox tradition and artistic modernism at the dawn of Russian art in the 20th century.

Roerich, Korovin and Gorbatov each left their homeland in the early Soviet years and joined the stream of creative émigrés scattered across Europe.

They took with them the cultural heritage of old Russia – its legends, landscapes and techniques – and translated them onto canvas for new audiences abroad. In doing so they not only preserved a piece of Russian culture through their art but also made their paintings timelessly bridges between East and West.

This is the background to their artistic legacy and why their work is collectible and inspiring today.

Nicholas Roerich: Mystic Symbolism and Cultural Vision

Roerich’s symbolist vision was often spiritual and bold. In his painting “And We Continue Fishing” figures are silhouetted against a sunset, fishing. Roerich was a polymath – a painter, archaeologist, writer, philosopher – his art is steeped in history and spirituality. Born in 1874 to an educated family in St Petersburg, Roerich grew up in the midst of Russia’s Symbolist movement, where the mystical and otherworldly were revered.

– a symbolist depiction of timeless ritual and spiritual endurance in Russian art of the 20th century

Early on he became obsessed with the distant past and the spiritual heritage of Eurasia. He studied painting at the Imperial Academy of Arts and also law, moved in the same circles as Diaghilev. It was Diaghilev who included Roerich’s work in a 1906 exhibition in Paris where the West first saw Roerich’s epic landscapes that seem to hum with the “mystery of nature, especially prehistoric nature” (britannica.com).

Roerich quickly gained fame not only as a Russian painter but also as a talented stage designer. He became perhaps best known for his work with Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, providing monumental historical sets and costumes for productions that needed an authentically Russian touch. His most celebrated contribution was the costume and stage design for the 1913 premiere of Igor Stravinsky’s ballet The Rite of Spring, where Roerich’s imaginative evocation of ancient Slavic ritual stunned Parisian audiences.

A few years earlier, he had designed the set for Alexander Borodin’s opera Prince Igor (1909), including the vividly imagined “Polovtsian Dances,” transforming theatrical stages into mythic landscapes of the 12th-century steppe (en.wikipedia.org). These achievements in theatre were not mere decoration; Roerich approached stage design as an extension of his painting, an opportunity to create scenic evocations of the past that immersed viewers in the beauty of bygone eras (britannica.com).

Outside the theater Roerich painted a lot. He is often considered one of the main representatives of Russian Symbolism in art. Along with contemporaries like Mikhail Vrubel and Mikhail Nesterov he put spiritual symbolism and enigmatic subjects into his paintings. Many of his early works are about ancient Slavic legends, saints and folk tales. For example his painting “Guests from Overseas” (1901) shows Viking age ships arriving in Russia’s lands, part of a series on the beginnings of Rus’.

This symbolist masterpiece portrays the legendary arrival of Viking ships in early Rus’. Bold colors, decorative forms, and mythic storytelling mark Roerich’s unique contribution to Russian art of the 20th century.

Roerich also had a great respect for architecture and religious art – during his long travels across Russia he made an acclaimed series of architectural studies (1904-1905) of old Kremlin towers, monasteries and churches. He even tried his hand at designing religious artworks: he painted a fresco for the Church of the Holy Spirit in Talashkino and designed stained-glass windows for a Buddhist temple in St. Petersburg. Some of his church designs were so modern that the Orthodox authorities refused to consecrate the buildings. Such episodes show Roerich’s constant struggle against the boundaries – he wanted to renew Russian art by connecting it with both ancient roots and universal spirituality, even if it meant to clash with tradition.

Roerich’s spiritual interests only deepened with time. In the 1910s he and his wife Helena got into Theosophy and Eastern religions, read Hindu and Buddhist philosophy and incorporated these into life and art. His paintings from then on featured the Himalayas, Buddhas and other symbolic imagery of enlightenment. When World War I and the chaos of 1917 hit Russia, Roerich saw those events as apocalyptic and mystical, believing a new age might be dawning in the chaos. But the reality was harsh.

Roerich was a cultural preservationist at heart – he valued Russia’s cultural heritage more than any ideology and was actively involved in trying to save art and architecture during the turmoil. In 1917 he worked with people like Maxim Gorky and Alexander Benois in committees begging the new authorities to protect museums, churches and estates from vandalism.

The civil war that followed made it impossible and Roerich grew disillusioned as he saw the Bolsheviks’ indifference (and often hostility) to the old cultural monuments. By early 1918 he was ill and worried for his family’s safety so he left Russia – supposedly “temporarily” to Finland but in fact it would be a permanent exile.

In emigration, Roerich’s life took on a legendary quality of its own. After a stint in Scandinavia and England, he eventually traveled onward to the United States and then India, following his spiritual calling. In the 1920s, he led the Roerich Central Asian Expedition through the Himalayas, painting the majestic mountains and immersing himself in the lore of Tibet and Mongolia. Settling in the Kullu Valley of India in the 1930s, Roerich continued to create art that blended Eastern philosophy and Russian soul.

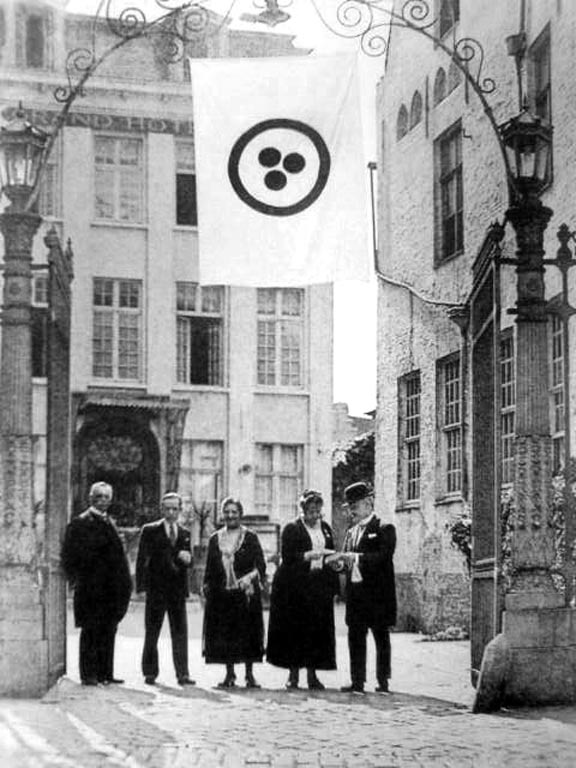

The Banner of Peace, created by Nicholas Roerich, flies above participants advocating for the protection of cultural heritage during wartime. This emblem became a lasting symbol of Roerich’s belief in art as a bridge between nations.

He became something of a guru-figure, founding the movement of Agni Yoga (a spiritual teaching) and corresponding with personalities worldwide. Despite being far from Russia, he never abandoned his mission of cultural preservation – in fact, Roerich initiated the famous Roerich Pact, an international treaty signed in 1935 by the U.S. and many nations that pledged to protect artistic and scientific institutions during war. For this effort to save the world’s cultural heritage, Roerich was even nominated multiple times for the Nobel Peace Prize (en.wikipedia.org).

Nicholas Roerich’s artistic legacy is as vast as his life story. Over thousands of paintings, he portrayed everything from ancient Slavic warriors to Himalayan vistas bathed in otherworldly light.

A consistent thread is symbolism – each canvas feels imbued with deeper meaning, be it a prayer for peace, a homage to nature’s grandeur, or an allegory of spiritual striving. Roerich’s use of rich, unearthly color and simplified, almost icon-like forms gives his work a hypnotic, contemplative quality (it was said some of his paintings have a “hypnotic expression” on viewers (en.wikipedia.org)).

Today, Roerich’s works are preserved in major museums – from the State Russian Museum in St. Petersburg to a museum dedicated to him in New York – and in numerous private collections worldwide. Collectors and connoisseurs value Roerich’s paintings not just for their beauty but for the cultural symbolism they carry. Each piece is a window into the spiritual culture of old Russia or the lofty ideals of Asia, rendered by a man who saw art as a bridge between peoples. In an era when art can also be an investment, Roerich’s oeuvre offers something doubly precious: tangible aesthetic and historical worth, and an intangible inspiration that continues to enlighten and uplift.

Explore more: The Legacy of the Nicholas Roerich Artist: Visionary and Innovator — on the life, travels, and mystical vision of one of Russia’s most compelling cultural figures.

Konstantin Korovin: Impressionist Color and Theatrical Flair

Konstantin Korovin, born 1861 in Moscow, was a Russian painter and a leading figure of Russian Impressionism. If Roerich embodied mysticism and legend, Korovin embodied joie de vivre – the joy of life – through colour, brushwork and light. He was brought up in the heart of Russia’s artistic world. Korovin came from a well-to-do merchant family of Old Believers (a conservative Orthodox sect), and while this heritage gave him a respect for tradition, the young Konstantin was far more interested in art than in commerce.

He entered the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture at 14 and studied under masters like Vasily Perov (a great realist) and Alexei Savrasov (a lyrical landscape painter). There he met classmates who would also become famous artists – Valentin Serov and Isaac Levitan – and they formed a tight-knit group of talents who encouraged each other. Those early years immersed Korovin in the Moscow school of realist painting but he was always moving towards a freer, more light-filled way.

Painted after his first visit to France, this lively Impressionist scene captures the modern spirit and color that inspired Korovin to transform Russian painting. His Paris works helped introduce a new visual language to Russian art of the early 20th century.

A pivotal moment came when Korovin first traveled to Paris in 1885. He later recalled, “Paris was a shock for me… the Impressionists… in them I found everything I was scolded for back home in Moscow” (en.wikipedia.org).

In the boulevards and galleries of Paris, Korovin discovered the liberating brushstrokes and bright palettes of Monet, Degas, and Renoir – a style that back in conservative Moscow had been frowned upon. Encouraged rather than deterred, Korovin embraced Impressionism and made it distinctly his own.

Through the 1890s, he painted en plein air across Russia and Europe, capturing dappled sunlight and atmospheric moods. His style evolved into a rich blend: clearly Impressionistic in its loose, dynamic handling of paint and love of modern life scenes, yet often with a Russian sensibility in choice of subject (troikas in the snow, birch forests, bustling Moscow streets). He also experimented with the decorative elegance of Art Nouveau in some works, showing his versatility.

Korovin’s Hammerfest: Aurora Borealis (1894–1895) is a Russian Impressionist take on an Arctic subject. Painted after his trip to the far north, this night time harbour scene is lit by an otherworldly green Northern Lights above the Norwegian port. In the late 1880s Korovin travelled to the Russian North and Arctic regions – journeys that inspired a series of famous paintings. Works like The Coast of Norway, St. Triphon’s Brook in Pechenga and Hammerfest: Aurora Borealis (which is now in the Tretyakov Gallery) show the beauty of northern landscapes.

In Hammerfest the undulating bands of the aurora and the glow of lanterns on calm water are in a delicate balance of greys and blues. These paintings were praised for their mood and immediacy; they felt like sketches (“études”) but were complete works of art. Korovin loved to explore how light could change a scene – whether it was the midnight sun on snow or gaslight on a Paris boulevard.

While Korovin’s easel paintings earned him renown, he had an equally significant career as a stage designer and scenographer for opera and theater. In fact, Korovin became the preeminent Russian stage artist of his generation, bringing Impressionist color and innovation to dramatic productions.

His foray into set design began under the patronage of Savva Mamontov, a wealthy industrialist who ran a private opera house and artists’ colony at Abramtsevo. In the mid-1880s, Korovin was enlisted to design sets for Mamontov’s operas – including Aida, Lakmé, and Carmen – which allowed him to experiment with exotic themes and lush, theatrical effects. These early successes led to a prolific career in the major imperial theaters.

By 1900, Korovin was designing the Russian pavilion for the Paris World’s Fair (even earning the Legion of Honour from France for his work). He later became the chief designer at the imperial Mariinsky Theatre in St. Petersburg, and also worked with Konstantin Stanislavsky’s Moscow Art Theatre on drama productions (en.wikipedia.org).

Korovin’s approach to set design was revolutionary. Instead of the flat backdrops that just indicated a location, he created what he called “mood décor” – scenic designs that captured the feeling of the performance. For example, in the productions of Rimsky-Korsakov’s The Little Humpbacked Horse (1901) and Sadko (1906) Korovin’s sets were famous for their expressiveness and detail, and enveloped the audience in fairy-tale wonder.

He had a gift for telling a story on stage, using colour, light and composition just as he did in his paintings to move an audience. A hallmark was his ability to create the illusion of vast space and natural light on the tiny stage. Whether it was a moonlit Russian village or a grand Parisian café, Korovin’s sets made the audience feel the mood of the scene – a true marriage of painting and theatre. This innovation influenced set design in Russia and beyond, combining fine art with performing arts in new ways.

Life was not without turmoil for Korovin. During World War I, he served his country by applying his artistic eye to camouflage – literally. Korovin worked as a camouflage consultant for the Russian army, devising ways to conceal military installations at the front. Even amid war, he was often seen at the front lines, turning the interplay of light and shadow to practical use in a deadly context. After the war, the Revolution brought economic hardship. Korovin remained in Moscow briefly under the early Soviet regime, continuing to contribute to theater (designing new stagings of Wagner’s Die Walküre and Siegfried, and Tchaikovsky’s The Nutcracker in 1918–20).

But by 1923, with Russia in chaos and his health declining, Korovin made the difficult decision to leave his homeland. The progressive-minded Soviet Commissar of Education, Anatoly Lunacharsky, personally advised Korovin to go to Paris for medical treatment and to care for his ailing son (en.wikipedia.org). Ostensibly a temporary move, this trip became permanent exile when circumstances in the USSR deteriorated.

Painted during his exile in France, this vibrant nighttime street scene blends the energy of Paris with Korovin’s distinctive Russian Impressionist brushwork. His Paris paintings captured both the elegance of the city and the artist’s personal nostalgia.

In Paris, Korovin hoped to make a name for himself as an artist in the art capital of the world – but initially he faced huge problems. A big exhibition of his work was planned for 1923 to launch him in the West but in a cruel twist of fate the entire shipment of his paintings sent from Russia was stolen en route. He was left financially ruined, almost penniless overnight. To survive the 60-something master had to paint non-stop. He painted numerous canvases of “Russian Winters” and “Paris Boulevards” – charming scenes of snowy villages and Paris nightlife – to pay the bills.

These works, sold to private buyers, kept him afloat and ironically became popular as they captured a nostalgic Russia and an elegant Paris through Korovin’s eyes. Later on his fortunes improved a bit. He continued to design for theatre internationally, designing sets for opera houses from Europe to America. One of his most famous late works was the scenery for The Golden Cockerel in Turin, a production that got great reviews for its imagination. But even as his art reached new audiences, Korovin remained homesick for the Russia he had lost.

He lived modestly in Paris until his death in 1939, just before World War II started again. Fittingly he was buried in the Sainte-Geneviève-des-Bois cemetery near Paris – a cemetery for many Russian émigrés, among birch trees that reminded him of home (en.wikipedia.org).

Korovin’s place in art history is secure. In Russia he is considered the first and foremost Impressionist of the Russian school, a man who brought the light and colour of Western European art into a Russian context. His paintings of busy Parisian cafes, flower stalls, sleigh rides under street lamps, and quiet Moscow courtyards still enchant in galleries around the world. Major museums like the Tretyakov Gallery and the Russian Museum have his works in their collections and his theatre designs are preserved in archives as masterpieces of stagecraft. For collectors Korovin’s paintings are forever desirable: decorative and deep, full of movement and mood.

A Korovin oil of a Paris boulevard at night or a winter landscape can still command attention in any collection – not just for its beauty but because it tells the story of an artist who bridged two cultures. His art reminds us that even in times of great change the human impulse to capture life’s moments in colour and light is priceless. So investing in Korovin’s work is not just buying a painting but a piece of cultural history that will bring joy.

Konstantin Gorbatov: Post-Impressionist Poetry of Old Russia

If Roerich was a symbolist mystic and Korovin an impressionist virtuoso, Konstantin Gorbatov represents the soulful post-Impressionist who captured the idyllic essence of Old Russia. Born in 1876 in the Volga River town of Stavropol (Samara province), Gorbatov grew up surrounded by the kind of scenery that would later populate his canvases – churches with onion domes, humble wooden houses, rolling hills and birch groves by the broad Volga waters (russianartgallery.org).

These early impressions instilled in him a heartfelt desire “to create” art out of the beauty of the everyday Russian landscape. Unlike Roerich and Korovin, Gorbatov came from a more provincial background and initially pursued a practical career, studying civil engineering in Riga in the 1890s (en.wikipedia.org).

But the call of art proved stronger. In 1904 he moved to St. Petersburg to enroll in the Baron Stieglitz School for Technical Draftsmanship, and soon after he gained admission to the Imperial Academy of Arts. There, he first studied architecture, but quickly switched to the painting department under landscape painter Nikolay Dubovskoy.

This evocative village scene combines expressive brushwork with a nostalgic vision of old Russia. Gorbatov’s post-Impressionist palette and lyrical treatment of light and architecture define his unique place in Russian art of the 20th century.

Gorbatov’s talent flourished; he earned a scholarship that allowed him to travel to Italy, where he painted in Rome and on the island of Capri – soaking in the sunlight and classical atmosphere that would inform his sense of color.

By the 1910s Gorbatov was already a well established artist in the Russian art world, showing with the Peredvizhniki (Wanderers) alongside the older generation of realists (en.wikipedia.org). His style at the time was a lovely mix of influences. Like many of his contemporaries he was touched by French Post-Impressionism – you can see Cézanne or Gauguin in the bold forms and expressive brushwork of his paintings. Indeed the influence of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism is strong in Gorbatov’s work, especially in his love of plein-air light and a bright, varied palette (russianartgallery.org).

At the same time Gorbatov’s subjects had “much in common with the art of the Wanderers” – he often depicted traditional Russian scenes and landscapes that the realist Wanderers loved. In other words he merged a modern style with old Russian themes. This resulted in paintings that are peaceful and poetic: sunlit church courtyards on summer days, quiet landscapes of river and forest at dusk, villages with festival banners.

One critic wrote that the artist himself described his style as a “celebration” and indeed Gorbatov’s paintings seem to celebrate the serenity and harmony of the world around him. Even when he painted abroad – seascapes of Capri, canals of Venice, or streets of Palestine – Gorbatov brought a gentle, lyrical approach but his homeland was always in his art.

In 1913, Gorbatov painted “The Invisible City of Kitezh,” a fantastical tableau of a legendary submerged city borne on a barge. This post-impressionist masterpiece combines Russian folklore with the artist’s observations of life on the Volga, merging mythic imagination with vivid detail (atsunnyside.blog).

This fantastical scene of a legendary holy city afloat on the Volga merges mythic storytelling with the artist’s deep familiarity with Russian architecture and river life. A poetic example of Gorbatov’s ability to fuse tradition and imagination.

One of Gorbatov’s most famous works, The Invisible City of Kitezh, exemplifies his unique ability to blend folklore and reality. The painting is inspired by an ancient legend of a city so holy that it was miraculously drowned under a lake to save it from invaders – visible only to the pure of heart. In Gorbatov’s imaginative rendition, the city’s towers, churches, and houses (adorned in colorful neo-Russian motifs) are loaded onto a gigantic barge sailing across a calm expanse of water (atsunnyside.blog).

The scene is bathed in soft, diffused light and pastel tones, characteristic of Gorbatov’s gentle color schemes. What makes the composition striking is how grounded it is in real observation: the barge (a belyana used for timber transport on the Volga) and the detailing of the wooden architecture are painted with the care of an artist who knows the Volga heartland intimately (atsunnyside.blog). Yet the concept is pure fantasy. In this way, Gorbatov’s art often lives in the interstice between the real and the ideal – capturing the actual beauty of Russian provincial life and elevating it into the realm of legend or dream.

Viewers find his work unforgettable because it triggers nostalgia for a Russia of the imagination, a land of tranquil beauty and fairy-tale charm.

The First World War and the Russian Revolution disrupted Gorbatov’s promising career just as they did for so many others. Gorbatov experienced the hardships of the era, and by 1922, faced with the grim new realities of Bolshevik rule (which had little interest in his style of art), he chose to leave Russia permanently. He first returned to his beloved Capri in Italy, joining a community of Russian expatriates there.

Four years later, in 1926, Gorbatov moved to Berlin, which became his base for the remainder of his life. In Germany he entered an active Russian émigré artistic circle that included the likes of Leonid Pasternak (the painter father of writer Boris Pasternak) and other displaced Russian artists. Throughout the late 1920s and 1930s, Gorbatov continued to paint and exhibit. He traveled around Europe, visiting the Middle East as well – journeys that provided new motifs but never diminished his love for painting Russian scenes. However, as time went on, his situation grew more difficult.

The rise of the Nazi regime in Germany in the 1930s was culturally stifling; Gorbatov’s idyllic and romantic art did not align with the regime’s preferences, and opportunities dried up.

The once-renowned artist found himself struggling financially, his art deemed out of step with the harsh new era. During World War II, Gorbatov, as a Russian émigré in Germany, was actually forbidden from leaving the country by the authorities – essentially trapped in Berlin during wartime.

Those years were tragic for him and his family. Gorbatov continued to paint privately, images of a peaceful world that must have seemed very distant amid the bombs. In May 1945, just days after the Allied victory in Europe, Konstantin Gorbatov died in Berlin. Shortly afterward, his grief-stricken wife took her own life, a sad footnote to the end of an era (en.wikipedia.org).

Yet even in death, Gorbatov’s connection to his homeland was reaffirmed. In his will, he bequeathed all his remaining artworks to the Imperial Academy of Arts in Leningrad (St. Petersburg).

05: Konstantin Gorbatov – Still Life with Pumpkins and Geraniums, 1930

After the war, these paintings were sent back to Soviet Russia and eventually found a home in a museum near the New Jerusalem Monastery outside Moscow, where they went on display to the public.

One can imagine local visitors in the 1950s standing before Gorbatov’s canvases of sunlit Volga churches and blooming apple orchards – scenes of a Russia that no longer existed in the form he painted, yet which lived on in art. In the years since, Gorbatov’s work has been rediscovered and appreciated anew.

Art historians note how his style sits at an intersection: he admired the Wanderers like Repin and Polenov (and was influenced by their robust drawing and earthy themes), but his color and brushwork owed much to the Impressionist/Post-Impressionist lineage. The romantic glow reminiscent of Arkhip Kuindzhi’s sunsets can also be seen in many Gorbatov skies (russianartgallery.org). This blend gives Gorbatov’s paintings a broad appeal – they feel classic yet modern, gentle yet emotionally resonant.

For Russian art collectors and enthusiasts, Gorbatov is a lesser known star who has been shining brighter over time. Not as famous to the general public as Repin or Shishkin, connoisseurs know the value of his beautiful and sophisticated work. A Gorbatov landscape brings elegance and serenity into a room – it’s the kind of art you can live with every day and see new beauty and details.

Moreover, Gorbatov’s work carries the story of an émigré who remained true to his vision despite the turmoil of history. Owning one of his paintings is owning a piece of that spirit. In recent years major exhibitions in Russia and abroad have reintroduced Gorbatov’s work to new audiences and they have done well at auction as the market for “Russian Impressionist” and émigré art has grown (a trend that reflects the broader appreciation of Russian culture).

Without using any market speak, one can say that Gorbatov’s paintings are collectibles – not just for their beauty but for the cultural nostalgia they contain. They remind us of a world of peace and beauty that artists try to preserve even as real landscapes and lives change irreparably.

The Enduring Power of Russian Art 20th Century

The stories of Roerich, Korovin and Gorbatov are the threads of the Russian art fabric from the end of the empire to the 20th century. Each artist carried a piece of the Russian soul: Roerich the spiritual and philosophical, Korovin the exuberant love of life and nature, Gorbatov the gentle reverence for homeland and tradition.

They were witnesses to an old world that was swept away – and through art they saved its image. They innovated within and beyond their genres: Roerich symbolism and exploration, Korovin impressionism and stage design, Gorbatov post-impressionism and folkloric narrative. The themes across their work – whether symbolism in Roerich’s mountains, impressionism in Korovin’s streets, or émigré art in Gorbatov’s vistas – continue to shape how we see Russian art’s contribution to world culture.

For today’s art lovers and collectors the legacy of these three masters is lightly inspiring and deeply educational. It shows that art endures beyond upheaval. A painting by Roerich, Korovin or Gorbatov is not just an image to look at; it’s a story of survival and continuity. Their canvases are time capsules of beauty and faith – faith in art, in culture and in the values those represent.

A deeply symbolic work, this painting reflects Roerich’s belief in inner light and cultural continuity. As a closing image, it encapsulates the shared mission of Roerich, Korovin, and Gorbatov: to preserve beauty, meaning, and soul through art — even in times of darkness.

Museums in Russia, Europe and America show their works as part of the world’s cultural heritage and exhibitions draw crowds who feel the historic atmosphere around each piece. In the world of art collecting the works of Roerich, Korovin and Gorbatov have lasting value that goes beyond trends. They are evergreen pieces for a connoisseur’s gallery or collection, not because of hype but because of quality and meaning.

To buy or simply to appreciate their art is to invest in cultural memory – to honor the rich Russian culture and the individual genius of these artists.In short, Nicholas Roerich, Konstantin Korovin and Konstantin Gorbatov show how art can both mirror and transcend history. Their artistic heritage is a heritage of beauty born of a particular time and place yet alive today.

They ask us to gaze at shimmering landscapes and ancient myths, to feel the emotion of a theatre scene or a sunset over water and to find inspiration in the knowledge that through art the spirit of a people and an age can live on. As we honour their work we remember that the canvas can be more durable than the canvas of history – and that is why their paintings quietly and without fuss are treasured in galleries, sought in exhibitions and loved by those who see art not just as decoration or investment but as a bridge between generations and a symbol of human creativity.

Collecting Russian Art from the 20th Century: Auction Highlights

While the works of Roerich, Korovin, and Gorbatov remain iconic, Aurora & Athena has also presented exceptional pieces by other Russian masters whose legacy continues to inspire collectors worldwide.

- Discover our previously sold painting by Nicolai Fechin, a celebrated figure of the Russian-American school known for his vigorous brushwork and expressive portraits:

Fechin – March Fine Art Auction - Explore the vibrant work of Filipp Malyavin, whose depictions of Russian peasantry burst with color and movement:

Malyavin – December Fine Art Auction

These sales highlight the sustained global interest in Russian art of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. At Aurora & Athena, we are proud to bring such works to market, connecting them with passionate collectors and connoisseurs.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why are Roerich, Korovin, and Gorbatov important in Russian art history?

Each of them represents a distinct facet of Russian art: Roerich’s mysticism and symbolism, Korovin’s impressionism and theatrical innovation, and Gorbatov’s post-impressionist lyricism. Together, they captured the essence of Russia during a time of cultural and political upheaval.

What styles or movements are they associated with?

Roerich is aligned with Russian Symbolism, Korovin with Russian Impressionism and modernist stage design, and Gorbatov with Post-Impressionism and late Wanderers-style landscape painting.

Did all three artists emigrate from Russia?

Yes. All three left Russia in the aftermath of the 1917 Revolution, continuing their careers in exile—Roerich in India, Korovin in France, and Gorbatov in Germany.

Are their works collected today?

Absolutely. Their paintings are held in major museum collections and regularly appear at international auctions. Their historical importance and stylistic uniqueness make them highly collectible.

What makes Russian émigré art attractive to collectors?

It captures the cultural spirit of pre-revolutionary Russia, often blending tradition with modern European influences. Many works also carry a sense of nostalgia, identity, and artistic resistance—qualities that resonate strongly with today’s collectors.

Where can I see more Russian artworks handled by Aurora & Athena?

You can explore past and upcoming auctions on our website, including works by Fechin, Malyavin, and others:

auroraathena.com/catalogs